By Eben Novy-Williams

University of Idaho President Chuck Staben thought he’d found the perfect solution.

In 2018 the state’s board of education had told its flagship university to cut its athletics expenses by $1 million. The result likely meant the elimination of three sports—women’s swimming, women’s soccer and men’s golf—and the addition of a low-cost sand volleyball program.

But looking at the numbers, Staben came to a different conclusion. By accounting for the tuition paid by non-scholarship athletes on those teams—money that went onto the school’s balance sheet, not the athletic department’s—he concluded that those programs were actually net profitable for the school. Instead of cutting sports to save money, Staben argued that Idaho should add them.

Expanding athletics would require the board to loosen its cap on how much general education revenue was earmarked for sports, but Staben felt that spending more would ultimately lead to earning more. He put together a 22-slide presentation which argued that while cutting sports would satisfy the cap, it would also cost the school $1.6 million per year. Adding men’s swimming, women’s triathlon and rifle, on the other hand, would bring the school an additional $843,000.

“And the board said, ‘No, we don’t want to see that,’” Staben said. “They wouldn’t let me present it.”

Staben was proposing an alternative way of thinking about the finances of college sports, one that’s been supported by economists for years but has yet to fully pervade the world of Division I presidents, provosts and athletic directors. If a university isn’t enrolled at max capacity, as most aren’t, some smaller sports like men’s track & field or women’s lacrosse actually make money for the school because of the number of athletes who pay their own way.

This reasoning may be more important now as universities begin to cope with two side-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, enrollment is expected to drop significantly across the country. Second, athletic departments, large and small, are being told to reevaluate their finances. And some are responding by slashing programs, even if it might not be what’s best for their students and their schools.

“It’s a failure of focus at the institutional level,” says economist Andy Schwarz. “If schools with under-enrollment are acting like schools with over-enrollment, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding of economics.”

Most Division I athletic departments budget in a silo, independent from the rest of the university. One of the biggest line items for most sports departments is student aid—the cost of the scholarships, waivers and tuition discounts. Those costs range from mid-seven-figures at small departments, all the way up to $28 million at Michigan, which is expensive and sponsors 29 sports.

That’s money that the school is essentially paying itself, and on the books it looks like the athletic department is paying the full tuition. In reality, the cost to educate those students, especially if they’re not taking the place of a student who would pay full price, is significantly lower. And nowhere in those budgets does it account for the tuition money that non-scholarship athletes pay to the school.

The NCAA groups sports into two categories: head count sports and equivalency sports. The head count sports like football and basketball, typically the ones that generate direct revenue, offer a set number of full scholarships. Athletes either have one or they don’t, and most do. The equivalency sports, or non-revenue sports, have a set number of total scholarships that can mostly be divided up however the school sees fit.

Take wrestling, which is an equivalency sport. The NCAA allows a maximum of 9.9 scholarships across a wrestling team, but the average team size is 33.1 athletes. That means a fully-scholarshipped wrestling squad still pays around 23 full-cost tuitions. Those athletes tend to be from out of state, which means they’re often paying a higher rate and likely wouldn’t attend the school if not for wrestling.

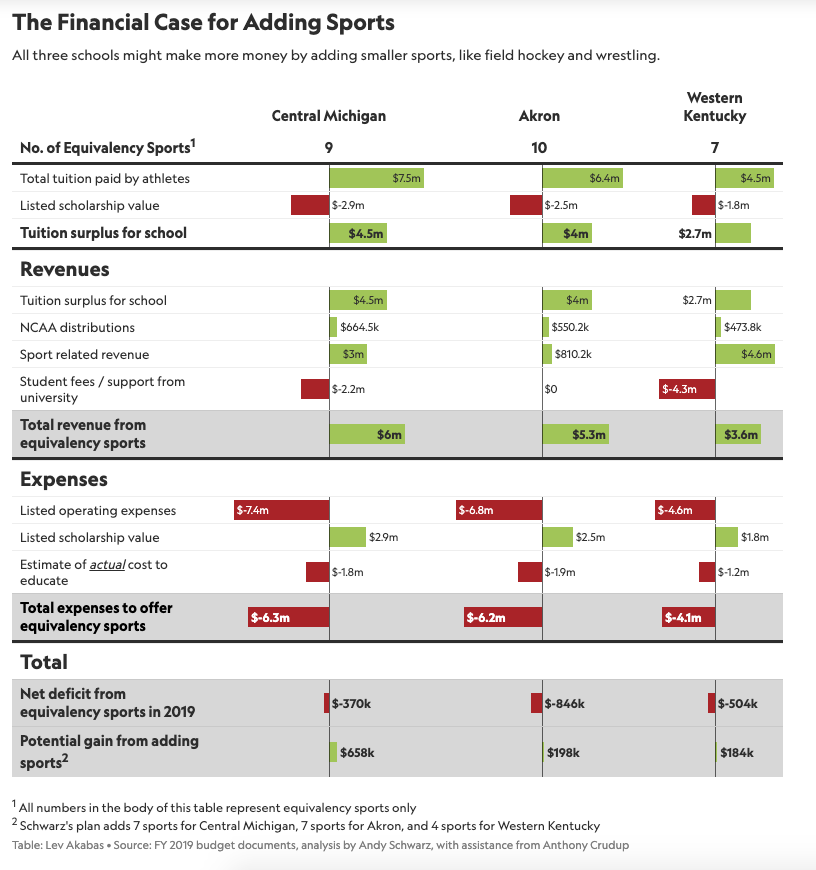

To illustrate this holistic view of accounting, Sportico asked Schwarz to analyze a few sample athletic departments. We chose three mid-sized Division I schools—Central Michigan, Akron and Western Kentucky—all of which have seen enrollment decline more than 10% in the past decade. Akron recently eliminated three sports because of COVID-19 budget concerns; Central Michigan cut one, while Western Kentucky has maintained its total.

Using athletic department budget documents Sportico obtained through open records requests, Schwarz recalculated the cost of educating athletes in those smaller non-revenue sports and reframed the revenue brought in by each sport to include NCAA distributions and tuition paid by athletes on partial or no scholarship. In all three cases, he found that the schools would make more money if they nearly doubled the number of equivalency sports they offered.

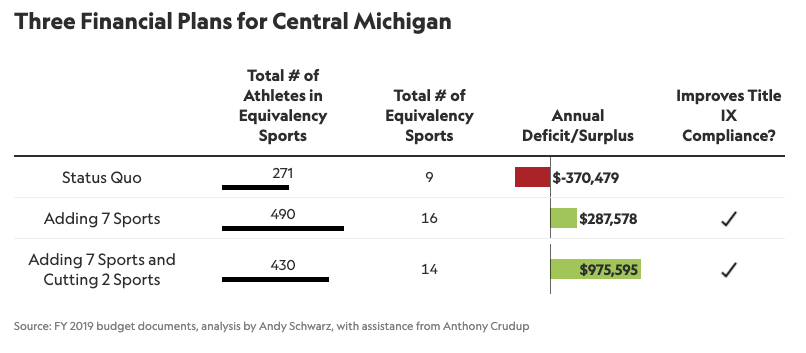

At Central Michigan, for example, men’s track and field/cross country, women’s field hockey, women’s lacrosse and women’s track and field/cross-country all make money for the school. In a world where Central Michigan could essentially clone seven of its nine non-revenue sports, Schwarz calculates the school could bring in an additional $658,000 per year. It would create an annual surplus for the entire group of equivalency sports, add opportunities for 215 more athletes, increase enrollment and improve the school’s Title IX compliance in both female participation and financial proportionality.

The results are even better with a more tailored approach. If Central Michigan could eliminate two equivalency sports and create clones of the other seven, the department would see an additional $1.3 million annually, per Schwarz’s math. In that scenario the school remains Title IX compliant, nets 159 more spots for athletes and ends up with an even bigger surplus from non-revenue sports.

Yet many schools are only cutting. More than 42 Division I programs have already been discontinued since the start of the pandemic, including two cut by Boise State on Thursday. More are likely on the way, especially as the viability of this year’s college football season hangs in the balance.

Enrollment drops will further muddy the waters. The number of people attending college has declined for eight straight years, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. A 2018 survey of admission directors, compiled by Inside Higher Ed, found that 90% of respondents were moderately concerned, or very concerned, about hitting their enrollment targets.

“I would imagine that for a lot of schools that are really struggling with enrollment, if they could find a way to double the size of the so-called non-revenue portion of the athletic department, they would make more money,” said Schwarz, who is co-founder of the soon-to-launch Professional Collegiate League.

This doesn’t apply to every school, and that incremental revenue is less of a concern for the biggest athletic departments, which make enough money from ticket sales and media contracts to easily cover other sports. In fact, no school in the so-called Power Five has eliminated a program during the pandemic.

That said, the siloed budgeting affects those schools in other ways. Excess revenue at big football schools are spent fully within athletic departments (on new stadiums, raises for coaches or other amenities), without regard to another area of need for the university.

Budgeting holistically also challenges a few generally-accepted myths about college sports—namely the widely-used stat that only 20-something athletic departments are profitable and the idea that only football and men’s basketball make money for their universities. The truth is school-specific, and much harder to calculate.

“It is really all in the details,” said Brian Goff, an economics professor at Western Kentucky who has studied athletics accounting for more than 30 years. “While I’m not a big fan of cutting programs based on flawed accounting, there are likely programs, particularly those with very low or zero revenues, and non-trivial coaches’ salaries and expenses, that it might make some sense to reorganize them as club sports that enlist volunteer coaches and travel on a narrower geographic basis.”

After Idaho’s education board chose not to hear Staben’s presentation, it kicked the can down the road. The University was given a three-year extension to comply with the board’s cap, and a month later the board announced it would not renew Staben’s contract after the 2018–19 school year.

“Now instead of $1 million over the cap we’re $1.5 million over the cap, so it’s just gotten worse,” said Staben, who is now a biology professor. “We still have the sports, and frankly, we should still have the sports, but the board should be thinking about this in a different way.”