Black student-athletes were often not allowed to participate in the mainstream competitions of the day.

It’s an explanation that has been repeated over and over until the words have lost much of their emotional effect. As with every aspect of life in America, segregation and racism once limited and blocked athletic opportunities for Black collegiate tennis players.

Social rules of the day did not stop Black people from playing tennis though. The sport was first introduced to students and staff at Tuskegee Institute (University) in the 1890s.

Tennis popularity slowly spread throughout the United States – with Black and white Americans – and by the 1930s Black student-athletes were competing at predominantly white universities in addition to Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

However, a Black student-athlete would not win the NCAA singles or doubles championship until 1965 when Arthur Ashe swept both titles. The landmark event came 82 years after the inaugural Intercollegiate National Championship (pre-NCAA).

It would take 11 more years until a HBCU would win an NCAA DII title. In 1976, the Hampton University men’s team carved a name for themselves in history and defeated defending champions UC Irvine to win the national championship.

HBCUs were familiar with carving out a spot for themselves. The institutions regularly worked to create opportunities for their student-athletes to shine.

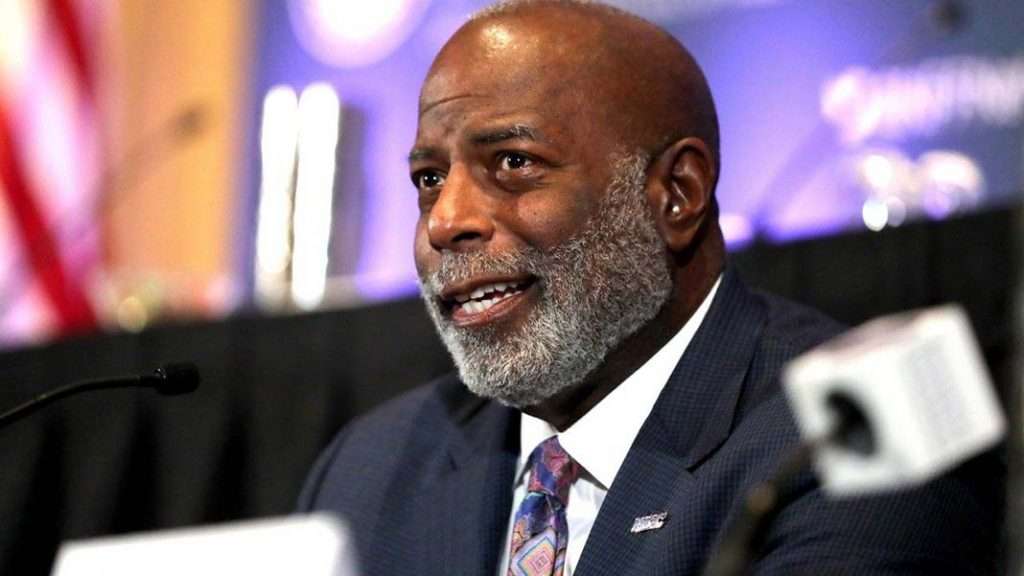

“Back in the forties, fifties, and sixties, HBCUs were not included in the mainstream tennis recognition of coaches and student-athletes — All-Americans, All-District, and things like that,” MEAC Commissioner Dr. Dennis Thomas explained. “So, we had to have our own championships. In terms of the best from HBCUs competing for the national title — that was our way of recognizing those outstanding student-athletes and coaches who were denied that opportunity on the national scale.”

Thomas’s own conference – the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference – has seen great success in the HBCU National Tennis Championship. The 2019 team champions hailed from the MEAC.

Despite their success, Thomas believes the achievements of student-athletes at HBCUs do not receive the level of recognition that they deserve.

“We’ve had some outstanding tennis coaches and student-athletes down through the decades,” Thomas said. “That goes back to Florida A&M and Althea Gibson.”

Some of the HBCU coaches he referenced were Howard University’s Larry Strickland and Hampton University’s Dr. Robert Screen.

Before retiring this past June, Strickland had served as head coach of the Howard Bison for 35 seasons. During that time he won three HBCU national championships and was named MEAC Coach of the Year 11 times.

Screen and his Hampton University program will forever be a part of tennis history. They remain the only HBCU to win a Division II NCAA national championship — a feat the Pirates accomplished in 1976 and 1989.

Part of Screen’s success may be due to his early adoption of international recruiting. His teams would be composed of the best players from across the world and, as a result, incredibly diverse.

The diversity found at HBCUs is one of the defining strengths of the institutions.

“You talk with white student-athletes, Hispanic student-athletes, and ask them what their experience has been — they would say outstanding,” Thomas said. “The community embraced them. They saw no difference in how they were treated. They saw no difference in how they were coached.”

Diversity, Thomas said, leads to a better working and competitive environment. The different perspectives make the community stronger.

In addition to teaching their student-athletes to be open-minded and accepting, Thomas said that the HBCU experience also taught students self-confidence, the value of hard work, determination, discipline, resilience, and the mental toughness to persevere even when you know that you have been mistreated.

One of the many challenges that HBCUs and their athletes have faced is underfunding. Thomas estimates that most HBCUs were underfunded for 150 years — some for even longer.

Working with fewer funds than major institutions, HBCUs do not always have the same resources for student-athletes and have a harder time with exposure, marketing, and recruiting.

“Kudos goes to the presidents, directors of athletics, head coaches, and student-athletes for persevering through arduous times and maintaining their sense of purpose, maintaining their sense of commitment, maintaining their sense of achieving their goals of being educated, and achieving their goals of participating in men’s and women’s tennis — and succeeding,” Thomas said.

Today, HBCUs – and all collegiate tennis programs – are facing a new challenge — the covid-19 pandemic.

“I think we are going through a metamorphosis right now because of the pandemic and collegiate programs and high school programs are under financial stress,” Thomas explained. “Programs are being eliminated and eradicated. Minorities are significantly impacted by this, so it is going to be a continued uphill battle for tennis as a whole.”

Support for HBCUs and their tennis programs can present itself in various ways. While HBCUs benefit greatly from financial support, Thomas said shining a light on HBCU tennis and the opportunities it presents to minorities also goes a long way.

Tennis has had issues attracting minorities – specifically Black athletes – to the sport. Many, including Thomas, attribute this to the lack of representation at the top levels of the sport. As compared with football and basketball, there are not nearly as many Black athletes succeeding in professional tennis.

As a community, Thomas said, we need to introduce tennis to Black athletes at a young age and expose them to all options to play at a higher level — including at HBCUs.

“We need everyone’s support,” Thomas concluded.

![Succession Success: Nadia Abdala, Head Women’s Tennis Coach, University of San Diego [Coaches Podcast]](https://wearecollegetennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Coaches-podcast-Graphic-Nadia-Abdala-218x150.jpg)